The Royal Military Canal And Its Twin

5th March 2021

This guest blog has been written for us by Bruno Comer (°Kortrijk). He studied law and spent his career as a business reporter in a bank. He has a special interest in British history and is looking forward to re-visiting England when it is safe to do so.

Ever wondered about some of the history behind why the Royal Military Canal was built? Did you know that there is an identical canal that was built for the same purpose over the English Channel in Belgium?

Check out the canal for yourself on our walking routes or cycling route from Hythe into West Hythe and onto the Marsh. Or if you are feeling adventurous take on the England Coast Path from Hythe to Folkestone.

The Information Of An Intriguer

The decision to build the Royal Military Canal may have been influenced by the French General Dumouriez. He had defected from the French Republican Army and had come to live in England. He highlighted to the British government the ease with which an enemy might land on the shores of the Dungeness peninsula. As a French military, Dumouriez had earlier been planning an invasion on England.

The British feared a French invasion which would not withstand the superiority of the Royal Navy. During the French Revolution a lot of noble people had left France, from the 1,200 officers of the ‘Marine Royale’, only 300 were left in 1792. This was one of the main reasons why the French fleet became so weak. The knowhow of the emigrated officers was crucial in naval battles.

To rival with the Royal Navy, Napoleon started to build as many ships as possible. Bonaparte’s intention had been to cross the channel in the sudden calm after a gale. Fifteen hundred barges packed with soldiers were to start from Boulogne, Wissant, Ambleteuse, 300 from Dunkirk, Calais and Gravelines, 300 from Nieuport and Ostend and 300 more filled with Dutch soldiers from Flushing. The French talked about a ‘poussière navale’, a ‘cloud of ships’.

Why The Canal Was Built

The purpose of the canal was to stop the enemy before they could form a bridgehead on British soil, however, usefulness of the canal was questioned. In 1823 the sight of the military canal caused William Cobbett, a member of parliament, to explode in anger to what he felt was the squandering of public money. ‘The French army had so often crossed the Rhine and the Danube and now it had to be kept back by a canal thirty feet wide at the most’, he argued. Cobbett wrote this once there was no question any more about a French invasion, this probably influenced his judgement. Most people think that the canal formed a tolerable military barrier.

An invasion never took place, and the canal became a means of transport. Troops were conveyed from the lock on the Rother to Hythe in four hours, performing the march from Rye to Hythe in one day which before would have taken two.

In 1816, the road beside the canal was finished, but was used by only the heavily laden narrow-wheeled waggons of the farmers. The road was in a too bad condition to have commercial value. The opinion of John McAdam was sought, the famous road builder who gave his name to a kind of road in almost every European language. He commented that the expenditure to improve the road could not be justified since the interests on the money needed for the investment could not be repaid from the tolls.

The Canal’s Brother

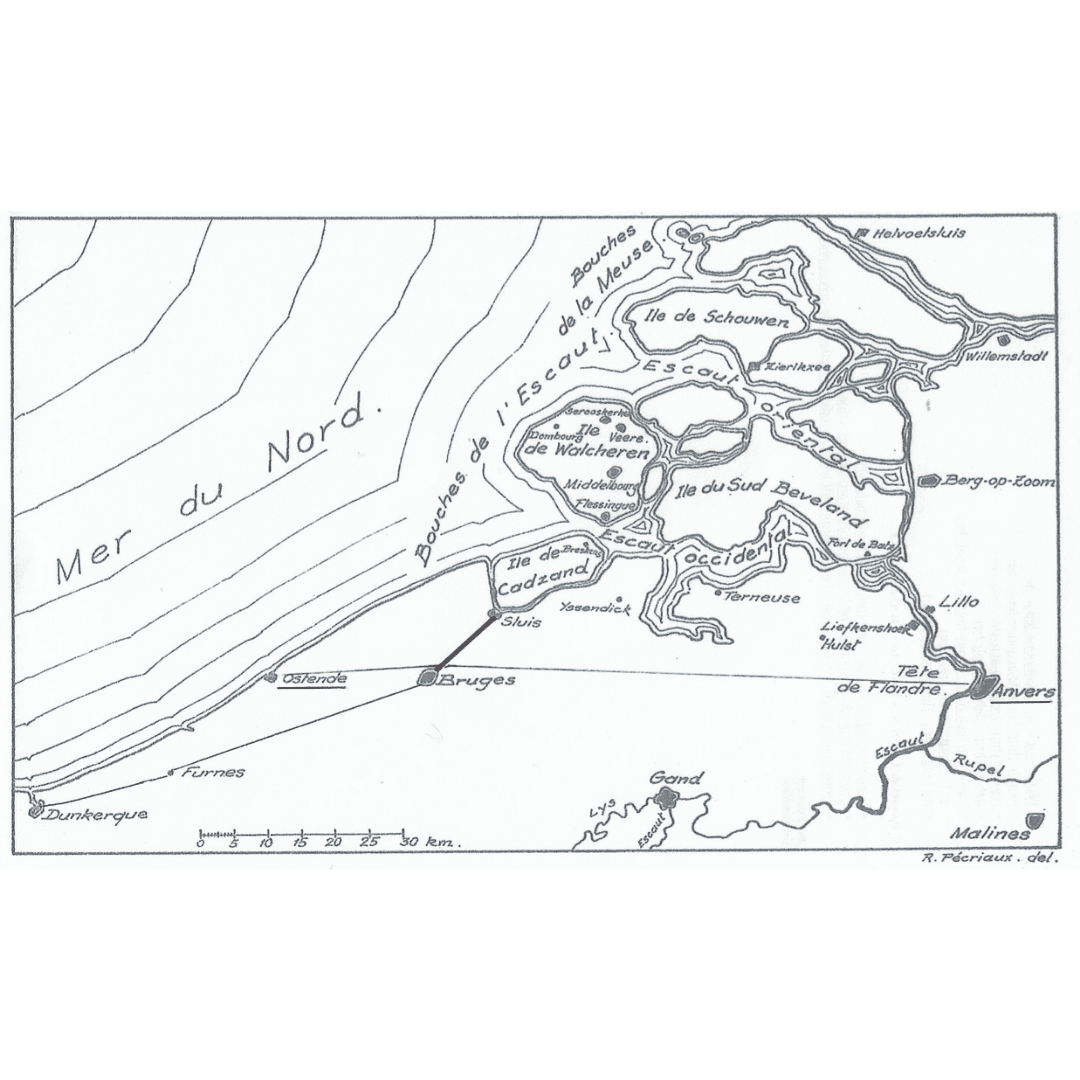

The Royal Military Canal has a brother on the other side of the English Channel. Another canal was constructed for similar reasons between Bruges (in Belgium) and Sluis (in the Netherlands). It was built for defensive purposes, although the French did not fear an English invasion that could threaten Paris, they were afraid of a British expedition against Antwerp.

After Trafalgar, the French reconstructed their fleet in the port of Antwerp as it was less vulnerable to suffer ‘raids’ of the Royal Navy. Moreover, the wind-direction was favourable for an attack on the eastern coast of England which was much more suitable for a landing of French troops than the ‘White Cliffs of Dover’. Therefore, Antwerp was called ‘a pistol pointed at the heart of England’.

A possible scenario feared by the French, was that a British expeditionary force would land in Ostend and make their way 70 miles east towards Antwerp, (green line on the map). The British would destroy the port, the shipyards and subsequently withdraw.

The canal between Bruges and Sluis would block the route between the two ports (red line on the map). Thanks to this watercourse, Ostend was completely surrounded by canals. The decision to dig the canal was made in 1811 and at the fall of Napoleon in 1814, the works were far from finished.

The Dutch, who ruled over Belgium between 1814 and 1830, pushed the job through. But as the canal was conceived for military purposes, it had only poor economic value and was never broadened or modernized. As with the Royal Military Canal, it kept its sight from the early nineteenth century and now retains its recreational and ecological function.

Image Captions:

2nd Image – The Damme Canal, which is about 9 miles long, splits the medieval village of Damme in two. ©Tourist Office Damme

3rd Image – The Damme Canal forms one of the most beautiful landscapes in urbanised Flanders. ©Tourist Office Damme

Popular articles

Walking the Pilgrims Way

Experience the beauty of walking across the Kent Downs NL through the…

Inspiring Pub Walks In Kent

With spring just around the corner, now is the ideal time to…

Walk Leader Volunteer Opportunity

Discover how you can become a walk leader in Medway! Uncover the…