Pollinator Stories From Kent and Beyond

13th January 2023

Most pollinators and plants are now in their winter diapause (hibernating or in dormancy). Eggs, larvae, pupae or adults are quietly tucked out of sight – under bark, in roots or leaves, secreted in underground and aerial cavities. Seeds, bulbs and tubers are ready to swell and germinate, responding to longer day length and warmer weather.

Winter may be the season for rest and reflection, it’s also a great time for story-telling. Here are a few tales of two Kent naturalists and scientists who have enriched our understanding of pollination and the natural world through their careful observations and research.

Charles Darwin is world-renown as one of the greatest naturalists and biologists of all time, and as the founder of the science of evolutionary biology, in particular through the publication in 1859 of the formative work, on the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Darwin spent decades in Kent and around the world, carrying out prolific and careful observations and analysis of geology, plants and animals, and the interactions between them. This tireless and meticulous work led him to question how species form and change over time, and to marvel at the interconnectedness of life.

From childhood, Darwin collected and studied many different insect species particularly beetles and moths. This obsession continued as a student at Cambridge and into his famous voyage as the naturalist on board the round-the-world expedition of HMS Beagle. As one example, Darwin was fascinated by the diversity of over 500 beetle species that he collected on the Atlantic island of Madeira, almost half of which were wingless species. He theorised that flightlessness occurred through natural selection and conferred an advantage, preventing foraging, wingless beetles from being blown out to sea on this constantly windy island. Many decades later, scientists tested this hypothesis on other flightless beetle species from different oceanic islands, and established that Darwin’s suggestion was correct.

Black blister beetle. Photo credit: David Hill, Creative Commons.

Later in the Beagle voyage, on the island of Madagascar, Darwin discovered an orchid species with nectar present at the bottom of a flower-structure about 30cm long. Darwin predicted in an 1862 book on the Fertilisation of Orchids by Insects that a species of moth or butterfly should exist, with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar at the bottom of this orchid structure. No such species was known at that time of the prediction. This suggestion was further supported by another great evolutionary biologist, Alfred Wallace, (who also proposed the theory of evolution at the same time as Darwin) – from studies made on moths from the African mainland. 30 years after Darwin and Wallace’s suggestions, exactly such a moth species was eventually discovered in Madagascar and described in 1903: the moth has a wingspan of about 15 cm and a proboscis about 30 cm long, and was named in honour of Darwin’s and Wallace’s predictions Xanthopan morgani praedicta.

The hawk moth Xanthopan morgani praedicta feeding with its extensive proboscis on the Madagascan orchid, as predicted by Darwin and Wallace. Credit: NHM/Lutz Wasserthal.

Darwin continued to study orchids in Kent, around Down House in west Kent, where Darwin lived for 40 years. This house and grounds provided the domestic laboratory for many ground-breaking ideas about the interrelatedness of the natural world. In his woodland and ‘entangled bank’ of chalk grassland habitats at Down House, Darwin spent many hours walking, watching, thinking and recording the wildlife. He was amazed and fascinated by the huge variety of colours and shapes in orchid family. From painstaking observations, meticulous dissections of local and exotic species, and field experiments, Darwin concluded that orchids, unlike self-pollinating or wind-pollinated plants, relied on insects for pollination. He suggested that cross-fertilisation – in which one plant is fertilised by pollen from another – would increase a plant’s genetic fitness and provide the diversity needed for natural selection, leading to evolution and the development of new species. He hypothesised that the fascinating combinations of forms and colours in orchids all served the same purpose: to attract insects to achieve this cross-fertilisation.

Orchids of Kent. Credit: Kent County Council – Natural Environment and Coast Team

At Down House and its surrounding Kent countryside, Darwin was endlessly fascinated by the interrelationship of the natural world. He suggested that the abundance of flowering plants is directly related to the number of pollinating insects present, as suggested by this amusing quote: “The number of humble [bumble] -bees in any district depends on the number of field-mice, which destroy their combs and nests… Now the number of mice is largely dependent, as everyone knows, on the number of cats… Hence it is quite credible that the presence of a feline animal in large numbers in a district might determine, through the intervention first of mice and then of bees, the frequency of certain flowers in that district!”

To find out more about Charles Darwin, his extraordinary work and impact, and about Down House, click here.

Darwin’s House at Downe. Credit: Kent County Council – Natural Environment and Coast Team

Another Kent naturalist, who was an infant at the time of Charles Darwin death, was the entomologist and bee-keeper Frederick Sladen. Sladen grew up at Ripple Court near Deal, and although he never achieved the eminence of Darwin, he drew inspiration from the earlier Kent naturalist.

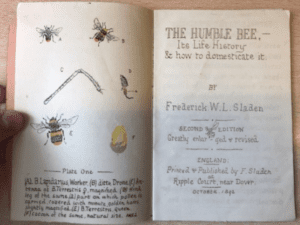

Sladen spent much of his youth exploring the countryside around his home, collecting field notes and observation about the wildflowers and insect life that were abundant then, and the relationship between humble bees (as bumblebees were called at that time) and the flowers they foraged on. He accurately observed the full life cycle of the bumblebee, from hibernating queens, to spring nest building, active summer colonies to the emergence of new queens and males. Captivated by the bees in the grounds of his home, he produced his first essay on them at the age of 15 in 1892, in his work The Humble Bee, it’s Life-History and How to Domesticate it.

Humblebee – Credit: Museum of English Rural Life

When his book was published, there were no detailed accounts of the life cycles of bumblebee species. Accompanying his notes were beautiful illustrations and photographs with occasional descriptions of the Kent countryside. Sladen provided a guide to distinguishing the different bumblebee British species (including the cuckoo bumblebees), and instructions on how to domesticate these important pollinators.

Sladen shared the enthusiasm of a naturalist with the accuracy of a scientist, and his book is still in print and available widely. It provides a fascinating historic record from the Kent countryside at the end of the nineteenth century. Sladen went on to keep bees and produce honey as a livelihood, and producing further publications on breeding honey bees. He later emigrated to Canada and continued to study pollinating insects including publishing a paper on hornets and eusocial wasps. Sladen died at the early age of 45.

Popular articles

Walking the Pilgrims Way

Experience the beauty of walking across the Kent Downs NL through the…

Inspiring Pub Walks In Kent

With spring just around the corner, now is the ideal time to…

Walk Leader Volunteer Opportunity

Discover how you can become a walk leader in Medway! Uncover the…